Let's Talk About It

Graphic by Manna Robertson

In light of recent cases of sexual assault on and around the UF campus, The Alligator listened the stories, explored the resources and followed the trends affecting students.

Survivors share their stories, encourage others to speak up

More than 30% of UF undergraduate women experienced nonconsensual sexual contact

By Melanie Pena

Graphic by Melanie Pena

Julia Mitchem weaved her way through the Gainesville Place parking lot as the lamp post light flickered. As she headed toward her apartment, the light trailed her steps.

A man sat at a bench. He stared at Mitchem.

As the 21-year-old UF journalism senior approached the picnic table, the man became more visible. He was masturbating.

“I just felt panic,” Mitchem said. “I called my boyfriend at the time and just started running and got away from there.”

More than 30% of UF undergraduate women experienced nonconsensual sexual contact by force or inability to consent since entering UF, according to a 2019 sexual assault and misconduct survey. This was an increase of almost 10% from the 2015 survey.

UF also reported 78 cases of Violence Against Women Act crimes in 2019, including domestic violence, dating violence and stalking, according to a 2020 annual security report. Only 38 cases were reported the previous year.

These numbers are not invisible to female UF students. Like Mitchem, many have experienced a sex crime themselves, or know a survivor. The numbers become most apparent in the messages many student-run social media accounts receive.

UF Girlboss is one of these accounts. The Instagram account was created by 20-year-old UF music composition sophomore Meagan Valliere and her roommate.

“It initially started completely as a joke,” Valliere said. “I don't think we posted a single serious thing. Being a victim of harassment and assault, I thought that it would be important to use my platform to eventually start doing serious posts.”

Valliere remembers when she first experienced sexual harassment at the age of 12 when a drunk man chased her down the street. Since then, men have followed her, stalked her and made inappropriate comments. The pattern of male harassmen molded into coercion and other gray areas of sexual assault as she reached adulthood.

“I've been basically assaulted by people I've been in relationships with,” she said. “Then that's really hard to report too, because where is the line drawn? You consented to this act, but you didn't consent to that act.”

Account followers messaged Valliere about their struggles with assaults in this gray area. Many feel guilty and confused. They weren’t attacked or forcefully penetrated, but they were taken advantage of and coerced into actions they didn’t want to do.

“They were in a relationship, and they were in love with these people and they took advantage of them and violated their consent and often didn't even ask and just went for things,” she said. “Even if they would speak up, it would be like [their boyfriend] pressed and pried and tried to coerce their partner into doing things that they wouldn't have otherwise.”

And with more messages flooding their inbox, the account shifted its focus to sexuality, consent and survivor validity beyond its meme-like posts.

The page shared the stories of two women who said a UF student drugged them at Grog House Grill. The women reported the crime to police, but the Grog camera footage was faulty and no arrests were made.

However, most of the stories of assault and harassment sent to the account were never reported to police.

“Feeling like there's an incompetent police force will deter people from even wanting to go in and gut-wrenchingly have to explain to people what has happened to them,” Valliere said. “People are not going to want to take that risk involved in going after the person that hurt them if it's going to be fruitless.”

After Mitchem’s experience, she called the police. Management at Gainesville Place told her it couldn't do anything about what had happened.

An officer explained to Mitchem that perpetrators will often start with public masturbation to test the boundary before working their way up to worse crimes.

“Then when it started happening more, that's when the panic started setting in,” Mitchem said.

Mitchem’s roommate, 22-year-old UF accounting senior Teagan Levee, found herself in the same situation about two weeks after Mitchem filed her report.

Levee and her girlfriend were walking home. When they passed the picnic table, a man sat there, masturbating.

She immediately called the police. The officer asked if the man had touched them. When she explained he hadn’t, she said the officer lost interest.

After the incidents, Levee and Mitchem began to post about what they witnessed. Friends reached out and shared their stories.

One friend told them she was swimming in the Gainesville Place pool when she noticed a man in the corner masturbating.

“It was scary because he walked in there,” Levee said. “It was getting scary to us because he's escalating. Before, he would just be there and watch people, but this time, he made his presence known to them.”

Levee, Mitchem and even Mitchem’s mother called the Gainesville Place office for weeks. They begged to move. They no longer felt safe, especially after discovering posts from years ago describing similar cases of harassment.

“This is an ongoing issue, and they're doing nothing,” Mitchem said. “And it's only going to get worse.”

The crime distressed Levee. It triggered memories from her freshman year, when she was assaulted at Grog.

“It made me feel so unsafe and powerless, and hopeless for what I can do, and how I can feel safe in my own home,” she said.

Levee had experienced revictimization, an effect of surviving sexual assault. Exposure to sexual assault puts survivors at higher risk of experiencing assault or harassment again.

Caroline Pope, a 23-year-old sociology senior, didn’t know about this phenomenon until she was assaulted a second time.

“I used to freeze like the first couple of times that I was assaulted,” Pope said. “Now, I actively am putting up a fight.”

One day in November 2020, Pope was celebrating with some friends in their apartment after a UF football game. Pope ordered an Uber home. Two male mutual friends were supposed to walk her to the Uber and make sure she was safe.

They checked her phone. One told her the driver canceled the ride. Pope asked them to reorder it. She got into the Uber, but she didn’t make it home.

“They didn't order it to my apartment,” Pope said. “They ordered it to a completely different location.”

From there, the men took her to an apartment.

The next day, Pope’s family came up to Gainesville to be with her. Pope decided to not report the crime but messaged the man who had raped her.

“I did message him about it though to tell him, ‘This is not OK,’” she said. “He responded with ‘I take it you don’t like me?’”

Later in May, Pope visited friends in Gainesville for a couple of days. She had been seeing a man she met through Tinder. Everything had gone well, and she liked him.

She had planned on meeting up with him again until he began to harass her over text.

When she went out to The Rowdy Reptile with friends a few nights later, the man was also there. She asked her friends to keep an eye on her.

“It was at the point where even the bartender was kind of concerned because I didn't look into it, and [the assaulter] was very touchy-feely all over me,” she said. “He wouldn't let me get away from his table, and I just wanted to leave.”

He managed to isolate Pope to coerce her into going home with him. The bar’s lights turned on, and the crowd swarmed out. She didn’t see her friends, so she left with him.

“There were things that I never would have agreed to that he did,” Pope said.

The next day, Pope was administered a rape kit. She spoke with a detective but decided not to pursue charges.

“I just want to have his name on the books that he's done this because he's gonna do it again,” she said. “I know he is.”

Pope blamed herself for a long time. But through therapy, research and advocacy, she has found a way to heal as a survivor.

None of these cases have been legally resolved, but the survivors are taking control of their experiences to prevent future similar cases.

Contact Melanie Pena at mpena@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter at @MelanieBombino.

Former employee embarks on legal journey against abusive work culture at Collier Companies

Anthoné Generis recounts cover-ups, settlements, non-disclosure agreements, retaliation, harassment and unwanted sexual touching

By Troy Myers

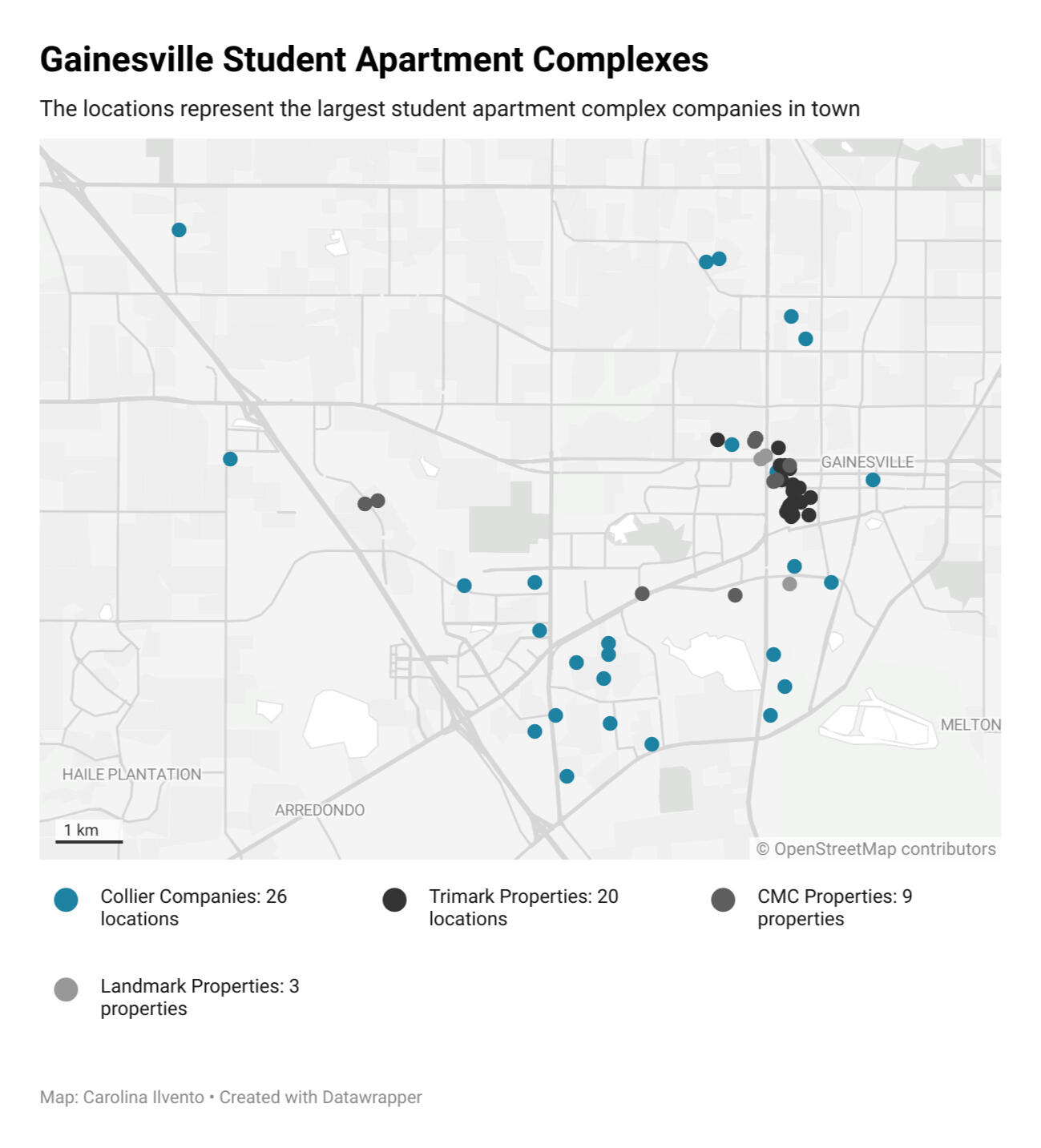

The Collier Companies is one of the largest student housing companies and employers in Gainesville, responsible for providing thousands of UF students with a safe home and hundreds more with a stable job.

Yet, residents and employees alike feel they’ve been let down, ignored, used and betrayed.

During the Summer and Fall semesters, residents of Collier apartments have brought safety concerns to front offices, witnessed serial problems with no tangible solutions, dealt with rising rent prices and protested the company’s decision to evict tenants receiving supplemental income.

Specifically, Collier-owned Gainesville Place Apartments, located at 2800 SW 35th Place, was the location of more than 250 calls to Gainesville Police Department within a nine month span in 2021.

Instances included rape and kidnapping, attempted break-ins, burglary and exposure to public masturbation. But the complex’s administration took no actions to improve security.

Collier residents have been witnesses, victims and survivors of crimes. Former employees have been, too.

Anthoné Gerenis was a young, homeless and hopeful Black man in Miami. Today, he’s a survivor seeking justice through a legal battle.

Gerenis was not yet 18 when he decided to move to Gainesville to attend UF. He became a tenant of a Collier apartment and was soon hired for a minimum wage job.

Over the summer of 2009, he embarked on his professional career with The Collier Companies. Along with the job came what he calls a nightmarish work culture — full of cover-ups, settlements, non-disclosure agreements, intimidation, retaliation, sexual harassment and sexual assault that he experienced firsthand in the years that followed.

Gerenis remembers being told this company is a family. In a way, they did become like a family for him — until he became a witness to their true colors.

With 26 communities in Gainesville alone, Collier claims to be the largest provider in the nation of student housing owned by a private individual. The company aims to double its number of apartment homes across the nation over the next decade.

It boasts having more than 12,000 conventional and student apartment homes. Collier has focused on providing housing in the southeastern United States, but it reaches as far as Georgia and Oklahoma. The company provides housing in some of the biggest college towns in Florida, namely Gainesville and Tallahassee.

Gerenis said everything that happens at Collier runs through one man: Nathan Collier.

Since Gerenis’ first day on the job and over the next few years, he said there were constant reminders that Nathan Collier was in full control of Gainesville and his employees.

Gerenis believes leadership starts at the very top of the company, and the habits and reputations of leadership trickle down to every facet of the company.

Early in Gerenis’ career, he wasn’t aware of compromising situations involving high-ranking employees.

Within two years of being hired, Gerenis was promoted. He was given an increase in pay and bonuses, the 2010 Office Team Member of the Year title, and he earned bachelor’s degree in telecommunications at UF in 2011. Then, he worked as a full-time employee as assistant manager at Gainesville Place Apartments.

There, he had direct interactions with students who made up the majority of Collier's workforce. He heard instances of these young workers experiencing issues with direct management, such as community and property managers, as well as senior management from the headquarters office — something Gerenis would soon experience himself.

Graphic by Melanie Pena

In December 2011, Gerenis was promoted to the headquarters office in Downtown Gainesville, located at 220 N Main St., and given the responsibilities of traveling to all properties the company owned in Florida, Georgia and Oklahoma. In the following months, Gerenis became more familiar than he wished with Michael Still, who managed the most extensive portfolio of properties and employees in the company at the time.

“Within six months of my promotion into headquarters, I became intimately aware of the culture of harassment and assault involving employees and student employees,” Gerenis said.

During Gerenis’ travels to different properties, coworkers complained about Still’s sexual harassment and unfair treatment. Following protocol, Gerenis reported it and HR told him it opened an investigation.

As of Dec. 5, neither The Collier Companies nor Nathan Collier could be reached for comment despite multiple phone calls, emails and a visit to two homes registered under his name.

In July 2012, Still was terminated from the company by executive team members, President Diana Miner, Vice President Mike Wilkie, Nathan Collier, CEO James Hogshead, President of Operations Jennifer Clince and HR Director Elizabeth Guynn.

Gerenis said he got to know Nathan Collier fairly well during his time with the company, even flying on his private jet together.

“Either he was completely aware of everything going on, which is completely terrible, or he was unaware, which is an unconscionable lack of control,” Gerenis said.

Although Still was separated from the company, Gerenis said other instances of sexual harassment, sexual assault and intimidation involving high-up employees continued. But he trusted these complaints were being handled properly.

A former executive leadership employee at Collier for just over a year confirmed these issues had been happening long before they joined the company.

“It’s very much like a cult environment,” said the former executive granted anonymity out of fear of retaliation.

Nathan Collier tweeted a quote by Todd Whitaker Oct. 19 that read “The culture of any organization is shaped by the worst behavior its leaders are willing to tolerate.”

The employee said Nathan Collier is a gifted public speaker who prides himself as a humble leader.

“I can tell you from my own personal experience that it is a show,” the former executive employee said. “It is all an act.”

After eight years working for the company, Gerenis left Collier for another job opportunity. In what Gerenis described as coincidental timing –– especially knowing the damaging information he had –– The Collier Companies offered a job to Still exactly five years after Still’s termination.

Just weeks later, Still became the vice president of operations, a position higher than he was in before his termination.

Gerenis later came to realize why Still’s rehire went so smoothly. He recalled an extremely high turnover rate at all levels of the company, meaning there would be few employees, if any, that knew of the complaints against Still like Gerenis does.

Gerenis was offered an HR position with Collier after about 10 months with his other job. Unaware of Still’s rehire, he accepted it. In Gerenis’ position, he learned all files are destroyed every five years, leaving no paper trail of any misconduct of employees — making the coincidence of Still’s timely rehire not so coincidental anymore.

While Gerenis worked in human resources at headquarters, he learned that the treatment of tenants was based on numbers rather than needs. He said tenants were described around the office as “just a number” and “expendable.”

He heard a motto frequently used in the headquarters office: “heads and beds” — to house as many tenants as possible.

“They’re seen as just an asset,” Gerenis said. “An ever increasing asset that we extract money from.”

After working with Still again around July 2018, Gerenis began experiencing sexual harassment.

Another anonymous, former high-ranking employee who worked with the company for about 10 years, said they mentored hundreds of people during their time with the company.

They said multiple young women working for the company would say they are experiencing harassment, mistreatment and intimidation and were afraid of reporting these claims to HR because there is “no confidentiality.”

As Gerenis learned more in his role at HR, he understood why there was no accountability for misconduct. He said reporting it fell on deaf ears. While working in HR, he saw reports shared with higher-up executive employees that would then come to be dismissed.

The same anonymous source had close interactions with Still and heard him call other employees derogatory names — Gerenis included. They said Still was “instrumental” in pushing out a pregnant woman from working with the company because she couldn’t fulfill her duties.

Gerenis said Still would ask him sexually-charged questions about his genitals and if he knew any other gay men in the company that “would be down to have some fun and looking for a daddy?”

By August 2018, Still began sexually assaulting him. His frequent displays of sexual arousal to Gerenis — touching his inner thigh and lower back — quickly turned into Still taking Gerenis with him on errands, locking themselves in the car and forcefully touching Gerenis’ genitals and assaulting him before Gerenis manually unlocked it and escaped.

In September 2018, Gerenis initiated a companywide sexual harassment training, but needed Still’s approval.

Still asked Gerenis again about other gay men in the office, becoming aggressive and sexually assaulting Gerenis.

Later in September 2018, Still insisted Gerenis join him for a work-related drink, despite Gerenis’ refusal. Still picked him up anyway from his company-owned home. This night consisted of unwanted sexual advancements, harassment, groping, assault and forceful consumption of alcohol.

Still told the waiter to continue filling Gerenis’ wine glass, using the company credit card to pay for the night out as he was the one to approve the transactions.

“He is responsible for the experience of his employees,” Gerenis said. “It’s his duty to be in control.”

About a year ago, Still was killed by a car while walking close to his house. While Gerenis expressed his condolences to Still’s family, he said he regrets not being able to sit across from him in a trial by jury.

In December 2018, after going to Still to report mold in Gerenis’ company home, Still turned their interaction into another uncomfortable and inappropriate situation, asking Gerenis if it’s worth his time to help fix the mold while winking and grabbing his genitals.

The mold was ignored again, as Still sexually harassed him later in the month for following up, Generis said.

After getting an estimate from Best Restoration, an outside company, out of concern for his health, Gerenis said Still continued to ignore the issue. When Gerenis confronted Still and asked to have the mold fixed again, Still denied him outright and then asked if he would be invited to Gerenis’ bedroom.

In March 2019, Gerenis’ doctors ordered an endoscopy, colonoscopy and requested a sample of the mold in the home and had procedures scheduled for March 19, 2019, which Collier responded to by asking Gerenis to vacate by the following Sunday, only six days after the procedure.

The same month, Gerenis learned of another coworker who Still locked his car while dropping him off at his company-provided house and sexually touched him against his will. He told Generis he didn’t trust other HR employees and knew nothing would come out of reporting it.

Also, Gerenis met with another coworker who confessed he felt unfairly treated by Still because he was the only heterosexual male on the team and wasn’t reciprocating Still’s advances.

“As much as I would love to pin all the blame on Mr. Still on what he did and his actions, he is a product of the environment which he was brought up in,” Gerenis said.

Feeling a complete lack of trust and failure by the company, Gerenis filed an official complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

On May 30, 2019, Guynn, the HR director, and Still threatened Gerenis in a meeting, telling him his mental fitness and anxiety are getting in the way of his role in the company and he should start looking for jobs elsewhere.

“The culture is ‘We can do and say whatever we want,’” the former, anonymous executive employee said.

So, he decided to immediately finish the EEOC complaint that night.

The following day, Gerenis was brought into Guynn’s office with Still. Gerenis expressed dismay at their attempt to use his anxiety as an excuse to say he is mentally unstable.

Then, Still fired Gerenis.

Still then winked at Gerenis as he left the office.

He walked Gerenis to his car and attempted to hug him to say goodbye. Gerenis said he backed away immediately and asked to be left alone, to which Still reacted by giving one last wink.

You should have kept your mouth shut. Good f---ing luck.

Gerenis left the office peacefully after putting up with years of harassment, misconduct, retaliation and assault. He said the company had failed him, just like they had failed countless employees before him and the inevitable employees that will follow. Gerenis is a survivor that experienced firsthand horrors of unchecked power and control.

“An environment of sexual exploitation, quid pro quo, harassment, plus a host of other activities all have been hidden with different cover-ups and corruption,” Gerenis said.

After years of abuse, he lost his home and job at a moment's notice. Now, he wants accountability for the ones taking advantage of Collier’s employees and tenants of their apartments.

“Unfortunately what happened to me is in the past and I can’t change that, but I am concerned about what the potential can be for the vulnerable student population,” Gerenis said.

In the following months after his termination, Gerenis said he received threats from other former employees and an employee still with the company who said he needs to watch his back. The employee still with the company after Gerenis’ termination said Still was furious and warned that he has powerful friends.

During the anonymous former executive’s time at the company, they got to know Gerenis as a hard-working, kind and professional employee.

The former executive employee noticed the real culture of the company within 60 days of working there, they said. They also had close, professional interactions with Nathan Collier and traveled on his private jet regularly.

“He rules that empire with an iron fist,” the employee said.

In hindsight, the anonymous former executive said other executive level employees absolutely took advantage of Gerenis because he was a young, Black man, citing the mold issue in the company-provided house that was kept to house the “African American employees.”

Over the 10 years the former high-ranking employee worked for the company, they learned the student workers, which make up a large percentage of The Collier Companies, are viewed as cheap and replaceable. They said Collier’s tenants are seen in the same light and under no circumstances would the company consider hiring security for apartment complexes.

The former high-ranking employee is worried about tenants being taken advantage of.

They want any present and future employees of the company to stand their ground and be careful so no more employees have to witness and experience what Gerenis had to. Change will hopefully come to the company because it will continue to happen, the anonymous source said.

Both anonymous sources described their time with the company as frustrating. The company will blacklist employees leaving the company if it’s on the wrong terms, they both said.

“Unfortunately, it's a million percent true,” the former executive said. “It just is. I would like to say that that’s the first time, but it’s not.”

Gerenis is being represented by attorney Kevin Sandersen and PR representative Laurie Watkins through the TIME’S UP Legal Defense Fund administered by the National Women’s Law Center, a 50-year-old gender justice organization.

The defense fund focuses on employees experiencing workplace sexual harassment and helping survivors connect with attorneys, assisting with legal fees and providing media assistance.

Director of TIME’S UP Legal Defense Fund Sharyn Tejani said roughly 6,000 people have reached out for assistance and about 4% are men. Tejani said she wants to bring more awareness to workplace sexual harassment and how common it can be.

Although it’s reported less, Tejani wants more people to know sexual harassment can happen to men, like in Gerenis’ case. She said she sees cases of sexual harassment based on gender, race, economic status and sexual orientation.

Watkins and Sandersen are assisting Gerenis with a legal complaint filed Feb. 15, in the U.S. District Court Northern District of Florida. Gerenis’ team understands the difficult road ahead, considering all the other survivors who are afraid to come forward or are in contracts that prevent them from doing so.

Gerenis’ team said the company’s power runs deep in terms of political connections and connections to other companies. Nathan Collier’s father, Courtland Collier, was a Gainesville City Commissioner for 18 years.

“The reach and power that [Nathan] does have is not just smoke and mirrors,” Watkins said. “It’s real.”

The case is scheduled for arbitration, a way to resolve disputes outside the judiciary courts, in February. Gerenis is seeking to recover damages for his loss of health insurance, income, housing and the verbal, mental and physical abuse he endured for years at the hands of Still.

Gerenis wants better training programs implemented in the company while bringing awareness to forced arbitration to protect student employees, specifically people of color.

Between Gerenis and the anonymous, former employees, they know of 24 other employees who experienced some form of sexual harassment or assault. They said some are afraid to come forward, some have signed non-disclosure agreements and some have been forced to move on.

“The minute you try to go and talk to outsiders, you are persona non grata,” Gerenis said. “They’re coming after you.”

Gerenis said he wants to keep fighting for all the silenced voices and bring forth a new standard for workplace culture. Although he’s seeking justice, he’ll always be forced to live with what happened to him and others.

Contact Troy Myers at @tmyers@alligator.org or follow him on Twitter @Troy_Myers1.

What happens when an Alachua County resident reports a sexual assault?

More than 30% of UF undergraduate women experienced nonconsensual sexual contact

By Isabella Douglas

No two sexual assault experiences are the same; but law enforcement across the county have similar response protocols.

Following the protocol, dispatchers head to the incident location upon receiving a call from a sexual assault victim. The victim then is taken to the hospital, where a rape kit is administered.

The hospital calls law enforcement and the victim service’s hotline, then the pressure is placed on the victim. How do they gather the words to explain the event they’ve not yet processed?

After a victim comes forward, several law enforcement agencies and victim advocacy groups throughout Alachua County are meant to help victims when they’re most vulnerable.

University Police Department

When and why a sexual assault victim reports their assault is up to them, detectives said. If a victim chooses to report their assault to University Police Department, they have three options: call its emergency or non-emergency line, send an email or online report, or walk into a police station, UPD spokesperson Rick Taylor said.

“The patrol officer will take the first report and be very brief with the victim so that they don't have to repeat necessarily the same thing to five different people,” said Bonnie Boland, UPD detective.

Officers work closely with UF Victim’s Advocates and the local hospitals to support sexual assault survivors.

Boland said UPD dispatchers want to know the location of the victim, the nature of the call, if the victim is still in danger and if the suspect is still present. It’s also kept brief to prevent the victim from reliving the moment.

If a victim chooses to pursue an investigation, a patrol officer will be sent to the location to write a report, collect evidence and preserve the crime scene. If a victim is nervous about what may be found on the scene, such as drugs, the department would prioritize the victim, Boland said.

The victim may then be taken to UF Health Shands Hospital to process a rape kit. A UPD victim service advocate may also be present to comfort the victim. At any time, the victim may ask to stop the procedures or investigation.

When a detective is assigned to the case, a victim service advocate may join when the victim is interviewed. The victim can also choose to only speak with a victim service advocate. In this case, the advocate wouldn’t relay any information to UPD against the victim’s will, Taylor said.

UPD victim advocate supervisor Veleta Roberts listens to victims share their stories. She collaborates with UF Counseling and Wellness, GatorWell and Housing to coordinate tools to help victims succeed at UF after his or her traumatic experiences.

“We are confidential, and we are free,” Roberts said. “We’re here to serve them if they want to come and talk to somebody. They are not going to be forced to speak with law enforcement, even though we are housed with the police department.”

Roberts works with the victim to place a no-contact order on their alleged abuser, especially if they live in the same residential hall or attend the same classes. In some cases, the alleged abuser must withdraw from those courses.

Taylor believes it’s important for victims to come forward so the department can actively pursue their cases.

“Most of the time these cases aren't happening on some dimly lit sidewalk,” Taylor said. “They’re happening in places where our students frequent.”

UPD’s office is located at 1515 Museum Road near Jennings Hall. The department’s non-emergency line is 352-392-1111.

Gainesville Police Department

If a victim chooses to open an investigation, the story would be told to law enforcement at the crime scene, said Laura Kalt, director of the Alachua County Victim Services and Rape Crisis Center.

It’s something she’s seen over and over. As of Sept. 9, 149 sexual assault cases have been reported to Gainesville Police Department. Reported cases have fluctuated among 174 in 2018, 153 in 2019 and 129 in 2020.

“Someone who does report to the Gainesville Police Department is very likely going to have an officer and advocate working together, getting to know them, helping them make this report and get through the experience of just having to relive the details,” Kalt said.

Victim services workers need to build a rapport with the victim because retelling their stories can be retraumatizing, Kalt said. Above all, she said, putting the victim’s needs first is important.

While working with GPD, she has watched the detective discuss the victim’s options of how to recount their story.

If you feel like you can get through 10 minutes of retelling what happened, then that’s all we’ll do. If you want to tell me everything that you can and get it over with today, let's do that. We’ll spend hours together or however long it takes.

GPD’s office is located at 545 NW 8th Ave. The department's non-emergency line is 352-955-1818.

Alachua County Sheriff's Office

If a victim is uncomfortable, the Alachua County Sheriff's Office will try to assign a deputy by the victim’s desired gender. Victims who choose not to speak with police still have the option to speak with victims services.

Law enforcement will instead contact the reporting party, which is usually a nurse or staff member on duty, to gather evidence, such as the rape kit. Rape kits should be performed within the first five days of the occurence for the most accurate results, a U.S. Department of Justice report read. Examiners should stick to two swabs per collection area to avoid dilution of the biological sample.

ACSO policy states that police will not talk with the victim nor question the staff on what occurred.

If the victim decides to pursue legal action at a later date, police will compile evidence and investigate the assault further. After gathering evidence, the State Attorney’s Office will decide whether or not to prosecute.

ACSO is located at 2621 SE Hawthorne Road. The office’s non-emergency line is 352-955-1818.

Contact Isabella at idouglas@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @Ad_Scribendum.

Alachua County resources help sexual assault survivors cope with trauma

Organizations provide mental health and legal services

By Meghan McGlone

Organizations in Alachua County are standing by at all hours of the day to offer trauma support for sexual assault victims.

A few include Three Rivers Legal Services, Peaceful Paths and the Alachua County Victim Services & Rape Crisis Center — each offering a variety of services to victims of sexual assault.

Three Rivers Legal Services

Graphic by Melanie Pena

Three Rivers Legal Services provides help with restraining orders, also known as injunctions, for victims. The nonprofit works with victims on restraining orders for domestic violence, sexual violence, dating violence and other situations, Staff Attorney Lauren Sleasman said.

There are no income limitations for services that have to do with sexual assault or domestic violence, Sleasman said. Anyone living in Alachua County can seek help through them.

Working on injunctions gives Sleasman a sense of justice because she gets to advocate for victims, she said. The process can be emotional for involved victims, she said. Additionally, working on certain cases can be emotionally tough for herself, especially when she needs to stay level-headed for victims.

“Some cases were horrible enough that they linger,” Sleasman said. “I can clock out at 5 or 5:30, but those facts don’t go away.”

Sleasman believes stress relief can be found through therapy groups and private sessions. She also encourages people to seek help even if they haven’t reported sexual or domestic violence to the police or aren’t sure if what they’ve experienced counts as violence.

“As attorneys, we keep it in confidentiality,” she said. “It’s still an element of the case, even if they haven’t reported it to the police, even if they don’t want to, and it can still help them get an injunction if the issue is ongoing.”

Peaceful Paths

Graphic by Melanie Pena

Other organizations, such as Peaceful Paths, provide free and confidential services to adults and children who’ve faced any kind of domestic violence, including sexual assault. The institution’s resources include emergency shelter, legal assistance for restraining orders, counseling services and other resources, Executive Director Theresa Beachy said.

All of Peaceful Paths’ services are free, Beachy said. They are available to anyone in Alachua, Bradford and Union Counties.

In her 21 years as executive director for the nonprofit organization, Beachy said it’s powerful to be part of the work that exists to save lives and create change.

“We know that the single most important thing that we as a community can do for survivors is to connect them with center services and to get that intervention in their life,” Beachy said.

It’s important to hold abusers accountable and create consequences for them, Beachy said, which is why Peaceful Paths’ protection of women and children is so important.

“We continue as a society to undervalue women and children and tolerate abuse for women and children,” she said. “We allow it because society has not created a good accountability system or a good punitive system.”

Alachua County Victim Services & Rape Crisis Center

Graphic by Melanie Pena

Victims can also seek help through the Alacha County Victim Services & Rape Crisis Center, where Cassandra Moore works as a project coordinator. The center has a 24-hour, seven-days-a-week helpline — a place for victims to anonymously report rapes and access other services.

Their gender-neutral services are available to anyone who identifies as a victim, Moore said, whether the situation involves roommates, coworkers, friends, partners, family members or anyone else.

When people call the helpline, Moore said workers will discuss victims’ physical health, whether they want to report the incident to law enforcement and if they are looking for shelter or other areas of support.

“We definitely just want to make sure we have a space that we can present them as many options as possible,” Moore said.

Psychologically, victims can face issues, such as hardships with relationships, sleeping and eating, Moore said.

Everyone heals from trauma differently, Moore said, and everyone’s different feelings of depression, anger, guilt or other emotions are normal and valid.

“It doesn’t matter what was happening, the assault falls on the person who did that crime without consent,” she said.

Contact Meghan mmglone@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @meggmcglone.

Faith Buckley contributed to this report.

What do numbers show about sexual assault on and around UF campus?

About 5% of reported rape cases result in arrest at UF

By Christian Casale and Omar Ateyah

Amid concern over recent cases of sexual misconduct on and around UF’s campus, data indicates that rates of such misconduct have remained consistent in recent years.

Between 2015 and 2019, University Police Department data shows reported cases of rape averaged more than 16 reports per year — following a change relative to UF’s steady student population. However, in 2020, a sharp decrease in cases coincided with the COVID-19 campus shutdown that shook up student life and housing.

With the closure of UF’s campus in March 2020, reports decreased by more than half compared to previous years — with seven cases reported throughout the year while campus housing remained closed for almost six months. So far this year there have been eight, according to UPD’s crime log.

The log shows that of the 97 total rape reports since 2015, only five have resulted in an arrest. Of the remaining cases, 13 were withdrawn and 60 are still pending.

A major issue facing the country with regards to sexual assault cases has been delaying the examination of the forensic evidence related to these cases, according to the Rape Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN). Legislation passed in Florida earlier this year, known as Gail’s Law, seeks to address the backlog crisis. The law creates a system by which rape kits can be monitored to provide victims updates on the kits’ progress through the justice system.

According to UPD’s public guidelines, the Clery Act definition of rape is the “penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus, with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim,” with no victim distinction based on gender.

Under the Clery Act, instituted in 1990 to ensure federal oversight in the disclosure of campus crimes by colleges and universities, UF and universities across the country are required to keep students notified about criminal activity that could threaten their safety.

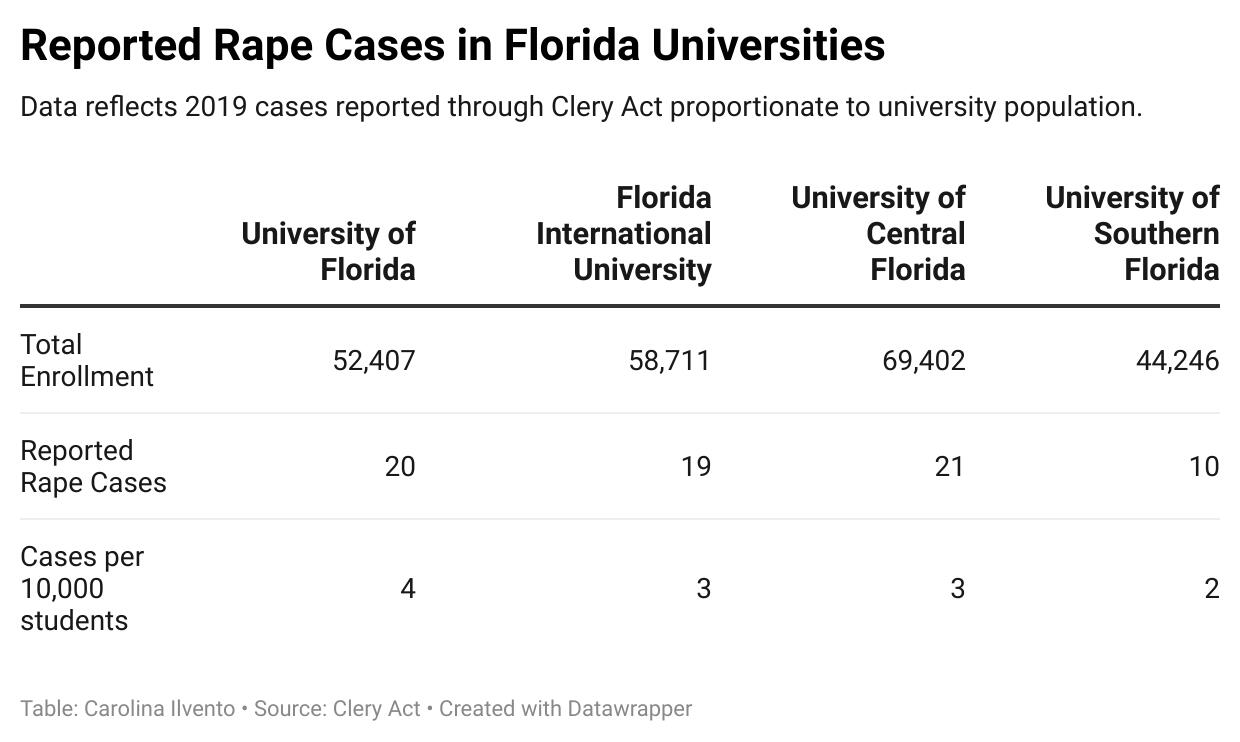

Out of Florida’s largest public universities — University of Central Florida, UF, Florida International University and University of South Florida — UF is first in reported rape cases proportionate to student population, according to most recent Clery Act data.

UF averaged nearly four cases per 10,000 students in 2019. The other universities had a close average of two to three cases per 10,000 students.

Not all instances of rape and sexual assault at UF are reported to the university, as many victims of sexual assault do not come forward with their stories. Therefore, no discussion of sexual assault data can provide a complete picture of the crisis.

According to a study by The Association of American Universities, one in four female undergraduate students and 13% of all university students will be a victim of “nonconsensual sexual contact by physical force or inability to consent” during their university experience.

Comparing the study’s estimates to the 2019 UPD crime log would mean less than 1% of victims filed a report after their rape.

The data required for disclosure is generally limited to crimes that occur within university property within a mile away from campus borders.

At UF, the Clery Act covers all crimes that occur either on UF’s campus or in housing complexes that are “reasonably contiguous,” said Kate Moore, Assistant Director of the UF Office of Clery Act Compliance. This includes all on-campus residence halls, the three off-campus student housing facilities owned by UF — The Continuum, Infinity Hall and Tanglewood Village — and Greek life houses, Moore said.

Although not included under the Clery Act, students may sometimes also receive Timely UF Alerts, or phone notifications of notable crimes, that took place off campus.

Notifications of off-campus criminal activity are generally sent out if the incidents involve students. The university and city police departments maintain a level of coordination to ensure UPD is notified of relevant off-campus criminal activity involving students, said AnnaLee Rodriquez, UF’s Office of the Vice President for Business Affairs spokesperson.

A UPD supervisor or a member of UF’s Office of Clery Act Compliance would decide what constitutes a timely warning based on standard guidelines, Rodriquez said.

“It is all based on the legal standard for issuance,” Moore said. “It's something that has that element of an ongoing or continuing threat to the campus.”

There is not complete consistency between rape data reported under the Clery Act and the number of rape cases included in the UF crime log.

Like any other university that receives federal financial aid, UF must report timely warnings to “all members of the UF community” for potentially ongoing and dangerous incidents in and around its campus.

Contact Christian Casale at ccasale@alligator.org. Follow him on Twitter @vanityhack.

Contact Omar Ateyah at oateyah@alligator.org. Follow him on Twitter @OAteyah.